The Post-War Years: Hanly Funderburk

Dr. Hanly Funderburk became Auburn's twelfth president in April 1980, and almost immediately became embroiled in controversy.

By Marcia L. Boosinger

Hanly Funderburk became president after a highly politicized search in which Governor Fob James disagreed with some trustees and faculty members over the final choice for the position. The search process and financial difficulties faced by Auburn in the early '80s, as well as his management style, made Funderburk’s years as president difficult.Funderburk was born on June 19,1931, in Carrollton, Alabama, and received his B.S. and M.S. degrees in botany from Auburn and a Ph.D. in plant physiology from LSU. He returned to Auburn and moved through the ranks from full professor to chancellor of Auburn University at Montgomery by 1978.

After President Philpott announced his resignation, the board appointed a search committee to identify his successor. Governor James supported Rex Rainer, former head of the Civil Engineering Department and his state highway director. The majority of the faculty and several board members favored Steven Samples, a vice president at the University of Nebraska. Hanly Funderburk, then chancellor at AUM, was also a candidate. The board met in March, 1980, to make a decision and Rainer failed to receive the nomination. Samples and Funderburk each received six votes. The governor disbanded the search committee and eventually convinced all but one member of the board to support Funderburk. Samples stepped aside at the last moment and, by a vote of 10-1, Funderburk became president on April 7.

Funderburk reported that the board gave him two goals early in his administration: improve the financial situation of the university and initiate a capital campaign. He began work on the first goal by holding a meeting with the general faculty at which he apprised them of imminent budget problems and called for "belt tightening" within the university. In order to improve university finances he centralized many of the fiscal operations of the university and instituted the first financial management system. During his first year, Funderburk oversaw the completion of the stadium expansion and student housing projects, the awarding of contracts for relocation of a new physical plant, and the beginnings of plans for the new student activities building. Addressing another of the board’s goals, he began a capital fund drive in his first year to address plant maintenance needs. Accreditation crises in the Colleges of Engineering and Veterinary Medicine soon after his appointment were resolved shortly after the conclusion of his term through renovation and construction projects made possible by fiscal management and fundraising.

However, deans and vice presidents felt they had decreasing control over reduced budgets and that fiscal control was separated from academic decisions. In an effort to get a bigger piece of the state appropriations pie, Funderburk proposed using weighted student credit hours to ask for funding from the legislature, making good on his commitment of "seeking the same level of state support for students at Auburn as at other Alabama institutions." Unfortunately, he did not communicate to the faculty that this formula would not be used for internal budgeting and they were convinced their departmental support would be based on degree production. Although he stated a commitment to academic freedom in his first meeting with the general faculty, six months after taking office he a sent out a memo stating that all employees should refrain from contacting board members without receiving approval from the president’s office. In April, 1981, he announced limited enrollment for out-of-state students without consulting with the Admissions Committee.

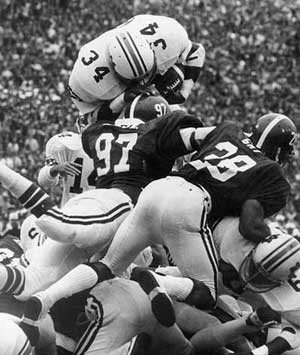

The Great Bo Jackson goes "over the top" to seal Auburn's 23-22 victory over Alabama in 1982, ending AU's nine year losing streak against its archrival.

The Great Bo Jackson goes "over the top" to seal Auburn's 23-22 victory over Alabama in 1982, ending AU's nine year losing streak against its archrival. Resignations from within Auburn’s upper administration followed the confidence vote. Within months of taking office, Funderburk had appointed James' administration member Rex Rainer his executive vice president, but Rainer resigned in December, 1980, after three months on the job, citing conflict with the administration over finances and enrollment. By May, 1982, Grady Cox, Rex Rainer’s replacement as executive vice president, and Taylor Littleton, vice present for academic affairs, both popular with the faculty, resigned, citing an inability to work with the president. The University Senate appointed committees to study the resignations, which found Funderburk’s leadership "dogmatic, intimidating, and manipulative" and "not highly principled." Funderburk replied that he served at the pleasure of the board and refused to resign.

In his official report to the faculty that same month, he pointed out the progress made on fundraising and plant maintenance, citing the more than $30 million raised by the Generations Fund campaign in only two years, an $18 million AUM library tower project and engineering building financed by a state bond issue, the new student activities building funded by a student-approved fee, and $5 million donated toward a second engineering building. In November, 1982, despite a more positive financial situation, the general faculty again voted no confidence in Funderburk 752 to 253, and in a second vote demanded that Funderburk resign or be fired. Funderburk again refused.

In December, the board met with President Funderburk and 17 of his top administrators. Thirteen recommended that he resign for the good of the university, but Governor James said, "We have not resolved the problem." Three days later, the University Senate again asked Funderburk to resign. In a show of support, the Alabama Farm Bureau proposed a rally for Funderburk and Farm Bureau offices around the state began circulating pro-Funderburk petitions.

In January, 1983, in his last board of trustees meeting, Governor James and the trustees agreed to a new administrative plan for Auburn that would have promoted Funderburk to president of the Auburn University system and created a position of chancellor for the Auburn campus to run the day-to-day operations. The University Senate censured the president, called the board "derelict" for refusing to remove Funderburk, and formed the "Auburn University Defense Committee" to take the fight over Funderburk as president to state and federal agencies such as the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS), the Alabama Ethics Commission, and to court if necessary.

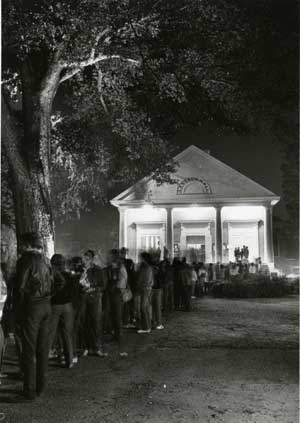

Students wait in a long line outside of Langdon Hall to attend the free movie in 1983-84.

Students wait in a long line outside of Langdon Hall to attend the free movie in 1983-84. Governor George Wallace took office early in 1983. At this time, trustee and state finance director Henry Steagall began to urge Funderburk to consider resignation, and he eventually agreed. After a closed session on February 26, 1983, in which the vote to accept Funderburk’s resignation was 11-1, the board met publicly to declare the chancellor system void and to announce that Wilford S. Bailey, former Auburn vice president, associate dean for research and graduate studies, and professor of veterinary parasitology, would serve as interim president effective March 1 while a committee of board members, advised by faculty, students, and alumni, searched for a new president. Governor Wallace pledged to stay out of the search proceedings. Funderburk would become the director of governmental and community relations at AUM.

When Funderburk left Auburn, he reported that the university was financially sound, and the capital campaign, begun fiscal year 1979-80, had grown to nearly $42 million of its $62 million goal. In addition, he left an active construction program primed for better economic times in Alabama higher education.