The Post-War Years: Ralph Brown Draughon

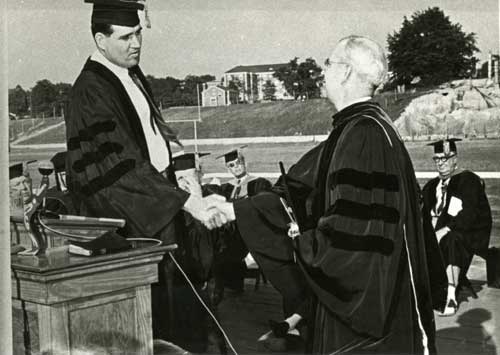

Alabama Governor James E. Folsom installs Ralph B. Draughon as Auburn's tenth president in May 1949.

Alabama Governor James E. Folsom installs Ralph B. Draughon as Auburn's tenth president in May 1949. By Martin T. Olliff

Following Luther Duncan’s death, the board of trustees named his long-time associate, Ralph Brown Draughon, acting president. In October, 1948, the board elected Draughon to the full office. His tenure laid the foundation for the complex institution Auburn University is today.Draughon was born in Hartford, Alabama, in 1899, received his bachelor’s degree in 1922 (along with the nickname "Knotty") and his master’s in history in 1929, both from API. He served as a school teacher and principal in rural Alabama until George Petrie appointed him to the API history faculty in 1931. President Duncan appointed him executive secretary to the board in 1937 and chief of instruction in 1944.

Draughon’s presidency began only four months after Governor "Big Jim" Folsom lost his fight to censure the Alabama Extension Service for illegally campaigning against him. Draughon used this incident to secure a trustees' resolution against partisan politicking, then applied a stronger ban to the entire college once inaugurated in May, 1949. This brought the Extension Service under his control, but made its legislative allies more suspicious than ever of Draughon’s agenda.

The new president faced another problem during his first months in office. The GI Bill had inundated API with students—doubling enrollment twice between 1944 and 1948. API’s physical plant and faculty were too small to handle the onslaught effectively. Throughout his tenure, Draughon worked with state and federal officials to get building and operating funds to improve campus facilities and its faculty, often engaging in politics he would have preferred to avoid.

Heavy enrollments also exposed API’s antiquated administrative structure and mission. Draughon modernized it by reorganizing schools and departments, establishing new offices, and bringing faculty into university governance. In 1947, for example, API created a separate Athletics Department divided into structural units, initiated the policy-making Graduate Council, published the first graduate catalog, hired 75 new instructors, and added 12,000 volumes to the library. For this effort, API won accreditation from the Association of American Universities.

President and Mrs. Ralph B. Draughon fish on Lake Martin on July 4, 1960.

President and Mrs. Ralph B. Draughon fish on Lake Martin on July 4, 1960. Financing these changes required skill and ingenuity. In the past, Alabama’s colleges had fought one another for a share of the legislature’s meager appropriation. At Draughon’s urging, the presidents of the state’s white schools presented to the legislature a series of unified budgets for higher education. This coalition was difficult to arrange and maintain; its leadership passed through the different presidents. Even Draughon himself broke ranks, once asking the State Building Commission to turn over two-thirds of its entire budget to API to finish a number of projects.

Draughon had a difficult relationship with the state’s legislators. Many feared his emphasis on broad education and his modernism. Others hated the control he exercised over the Extension Service. Enough others honored most of his requests. The stress of his position contributed to his 1955 heart attack.

Nowhere was Draughon more vulnerable to legislative manipulation than during the civil rights era. Desegregation haunted him his entire career, from the 1948 application of William Bell through the 1964 admission of Harold Franklin. As the 1950s progressed, there was not a more volatile issue facing Draughon’s meticulously crafted but delicately poised agenda.

Initially, Draughon worked with state and regional agencies to promote excellent but separate educational opportunities for blacks. After the 1954 Brown decision, he knew segregation’s time had passed, but acquiesced in the Auburn trustees' and the state government’s resistance to federal law. Draughon advocated handpicking a few black students who would enroll quietly, but the board required him to ignore applications from African-Americans until someone sued for admission.

Legendary Auburn football coach Ralph "Shug" Jordan signs his first contract in March 1951. Witnessing the signing are (left to right) President Ralph B. Draughon, new Athletics Director Jeff Beard and Business Manager W.T. Ingram.

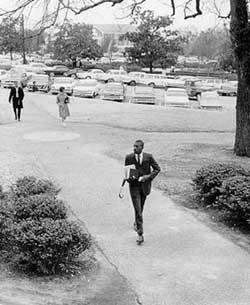

Legendary Auburn football coach Ralph "Shug" Jordan signs his first contract in March 1951. Witnessing the signing are (left to right) President Ralph B. Draughon, new Athletics Director Jeff Beard and Business Manager W.T. Ingram.  Auburn's first black student Harold Franklin walks near Samford Hall after enrolling in January 1964.

Auburn's first black student Harold Franklin walks near Samford Hall after enrolling in January 1964. Draughon, who received an honorary doctorate of laws from Birmingham Southern University in 1948, retired in 1965, after leading his alma mater through a turbulent period of growth and change. During his tenure, API grew into a modem university, very much in step with space-age America. Draughon oversaw the erection of 50 buildings, the doubling of on-campus housing, the inauguration of 16 doctoral programs, accreditation of the university from SACS and of individual programs from their respective organizations, and the increase to more than 40 percent of faculty with terminal degrees. Draughon died in1968 and is buried at Pine Hill Cemetery in Auburn.