The New South

by Dwayne Cox and Rodney J. Steward

The first Glomerata (Yearbook) was published in 1897.

Between the years 1872 and 1900, the Agricultural & Mechanical College of Alabama gradually emerged as a leading institution for the scientific study of agriculture and mechanical sciences. Like many land-grants, the A&M College faced an uphill battle in its efforts to carve out a niche for itself. Many state officials and educators, including some of the school's own faculty, doubted the efficacy of a curriculum devoted to the scientific study of agriculture. Heretofore, higher education in much of the United States was firmly rooted in the classical traditional, which emphasized the arts over the sciences. Universities prepared gentlemen for careers in the “respectable professions” of law, the ministry, and medicine, not as scientific farmers. Furthermore, only a narrow segment of the overall population attended universities, for cost of tuition and lack of preparation often barred the way for the vast majority.

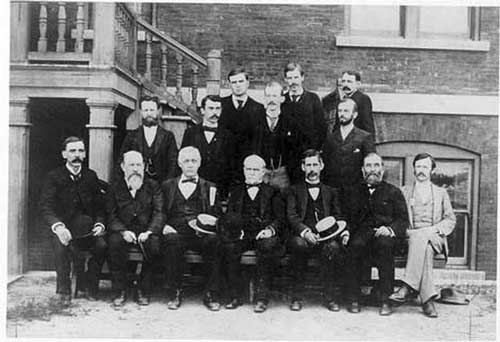

Auburn Faculty - 1890

Much of the school's success in modernizing Alabama agriculture in those early years can be attributed to the vision and dedication of two men: Isaac Taylor Tichenor and William Leroy Broun. Tichenor and Broun both served as president of the college in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Each played a vital role in the school’s development as a premier land grant institution.

On March 22, 1872, the board of trustees of the newly chartered Agricultural & Mechanical College of Alabama elected Isaac Taylor Tichenor the institution’s first president. Tichenor, a Baptist minister and Confederate veteran, was a staunch advocate of the scientific study of agriculture, which he viewed as essential for putting Alabama on the road to economic recovery.

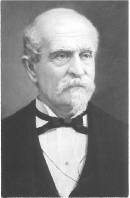

Dr. Isaac Taylor Tichenor

was president of the

Agricultural and Mechanical

College of Alabama

(now Auburn University)

from 1872-1882.

The following summer, Tichenor delivered his first annual report to the board of trustees. Tichenor reported that the school was in debt, the faculty unpaid, and financial resources were uncertain. Tichenor urged the board to employ a full-time professor of agriculture to oversee the school’s newly acquired farm, and warned that financial mismanagement and lack of resources threatened to compromise the school’s mission. Tichenor perceived that public misunderstanding could potentially stunt the school’s growth and therefore he requested that the board give an agricultural scholarship to one student from every county in the state, a move he believed would bolster recruitment, economic development, and public relations.

The school’s financial problems persisted throughout the decade of the 1870s. Tichenor believed the state’s mismanagement of the initial endowment financially crippled the school, and, moreover, the threat of unfriendly legislation portended an ominous future for the struggling institution. Tichenor called for the state to attend to the “wants of the college,” which included funds sufficient to train students to exploit Alabama’s natural resources. Furthermore, he predicted that if the state failed to provide leadership in this area, Alabama’s resources would remain undeveloped, or worse, exploited by outsiders, a code word for Yankees.

By 1877, competition between the University of Alabama and the Agricultural & Mechanical College for patronage had intensified. In January, Tichenor reported to the board that Alabama had reduced its tuition and lowered its graduation standards. Tichenor responded by requesting that the board drop tuition and create a boarding department to further lower expenses. Competition with Alabama was beginning to take a toll on the already financially strapped school. Tichenor frequently complained that that land-grant colleges, which prepared people for work in agriculture and mechanical arts, pursuits that employed the greatest portion of the population, received less financial support than other institutions and were relegated to an inferior status. Nevertheless, Tichenor was proud of his school's progress and often boasted that the school was the best land-grant institution in the South.

Toward the end of his term, Tichenor proposed a tax on commercial fertilizer. The school would receive a portion of revenue raised in return for chemically analyzing all commercial fertilizers sold in the state. Tichenor’s fertilizer tax passed the legislature, but was vetoed by the governor.

Tichenor faced many more battles with the state, and competition with the University of Alabama continued to escalate. Isaac T. Tichenor resigned his position as president of the college in 1882 and went on to pursue other interests. Throughout his decade-long tenure, Tichenor fought to secure a prosperous future for the school, which, by the time of his resignation, was beginning to sink deep roots in east Alabama.

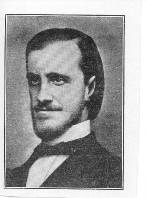

Dr. William LeRoy Broun

was president of the

Agricultural and Mechanical

College of Alabama and

later of the Alabama

Polytechnic Institue

(both now Auburn University)

from 1882-1883 and 1884-1902

Within a year of Broun’s taking office, the state legislature established a Department of Agriculture. This legislation provided that one-third of the net proceeds from the sale of commercial fertilizer tags be transferred to the land grant college for use by its mechanical and agricultural departments. In return, the college performed a chemical analysis upon all brands of commercial fertilizer sold within the state. The legislature further directed that a portion of the funds so appropriated be used for creation of an agricultural experiment station that would furnish information to the Commissioner of Agriculture for publication in monthly bulletins and annual reports.

On June 28, 1883, the board passed a resolution of appreciation for President Broun, who had resigned to accept another position. Earlier that month, Broun had issued his annual report, where he made recommendations regarding the future of the college and gave some indication of the reasons for his departure. Broun urged the board to focus the school’s curriculum on only a few courses, rather than diffuse their efforts into many. He believed that by doing so the school could provide something the state desperately needed, “an Institute distinct for teaching science and its application.” Many board members, however, were reluctant to embrace a purely scientific curriculum and opposed Broun’s recommendations.

Dr, David French Boyd,

president from 1883-1884.

Cadets in 1888

On June 25, 1884, the board unanimously re-elected William Leroy Broun as president, a position he held until his death. Broun moved quickly to solidify the position of agriculture and mechanical arts within the school’s curriculum. Within a few months, Broun recommended that the board hire a professor of practical mechanics. He also recommended that the school’s name be changed to the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, signifying an “enlarged sphere of educational work.” The board acceded to his first request and appropriated $5000 for the creation of a mechanical department. Shortly thereafter, the college catalog listed three courses of study, two technical and one general.

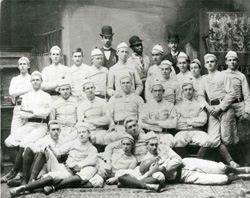

The 1892 football team... members unidentified

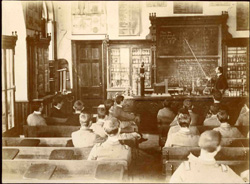

Analytical Chemistry Class, 1893