The Roaring Twenties and the Crash

Glomeratas currently available

on-line for this time period:

By Dwayne Cox and Rodney J. Steward

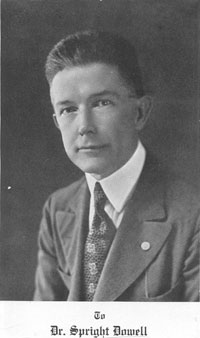

The thirteen years between 1919 and 1932 may have been the most turbulent in the history of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. They began with the controversial resignation of a long-term, popular president and the appointment of a successor who never enjoyed the full support of the college community. During these troubled years, API experienced a series of unsuccessful football seasons, an attempt to move the school from Auburn to Montgomery, the forced resignation of one president, political warfare with the University of Alabama, and charges of unethical behavior against the Cooperative Extension Service. Controversy turned to crisis at the end of these years with the onset of the Great Depression and with shortfalls in state revenues that crippled the college and hastened the downfall of another president who simply lacked the resources to cope with the financial emergency.Well before President Thach actually resigned, speculation regarding his successor abounded. Although Governor Thomas M. Kilby publicly disavowed any plans to replace him, privately he feared that finding a new president was inevitable. William F. Feagin, an API graduate and board of trustees member, desperately sought the position, but the president of the alumni association opposed him and advised Governor Kilby against his appointment. Eventually, the trustees appointed state superintendent of education Spright Dowell, who also served on the board by virtue of that position. Governor Kilby termed Dowell’s appointment “the wisest thing the trustees could have done.”

After a year in office, Dowell reported to the board of trustees that the long and distinguished service of President Thach made the job of his successor “delicate and difficult.” The situation was compounded by the disrepair of buildings and equipment, the college debt, and meager faculty salaries, which, at that time, were paid in quarterly installments. Dowell reiterated a statement first made in his inaugural address: API faced “the slow disintegration” that inevitably followed “a long period of undernourishment.” He called upon the state to appropriate $2 million for a massive building program during the next quadrennium, plus comparable increases in other areas of the budget. He argued that API’s contribution, past and present, to the state’s industrial development; relative lack of support from the state in the past; and the college’s responsibilities for teaching, research, and extension all justified his request for a massive infusion of funds.

By the close of Dowell’s second year in office, API faced a daunting new challenge, not to the school’s financial health, but rather to its location. On December 6, 1922, the executive committee of the board met in Governor Kilby’s office to review bids for various construction projects. Kilby reported that a group called the Montgomery Committee, headed by attorney Jack Thorington, wished to meet with the board before any new construction projects got underway in Auburn. Thorington and his group urged the executive committee to consider moving the school to Montgomery, a motion that Kilby apparently supported. Later, the committee met with Thorington, who produced a bill which he intended to introduce to the upcoming session of the legislature. The bill drafted by Thorington and his group called for the relocation of API from Auburn to Montgomery, but not before the city provided land and buildings for the campus. The trustees, led by Thomas D. Samford, flatly rejected the proposal and urged Thorington to cease all further agitation on the issue. President Dowell, who was absent at the first meeting, offered only a half-hearted resistance to Thorington’s bill. The president’s seemingly weak response cost him the support of the board, faculty, and the student body.

Dowell met with the board of trustees early the following year at the annual meeting, which marked the beginning of a general downturn in the efficacy of his policies and the popularity of his administration. Topping the board’s agenda was the mounting crisis caused by the resignation of football Coach Mike Donahue after a successful season. Dowell commented that Coach Donahue’s resignation was “viewed with alarm by practically the entire student body and a large majority of the alumni.” Making matters worse, Dowell stirred controversy when he recommended that all athletic funds reside in the college treasury. Three months later, Dowell became entangled in a political battle when he criticized a millage tax proposed by newly elected Governor William V. Brandon that would substitute for, rather than supplement, API’s current appropriation. The president stated that he was “unwilling to accept the responsibility for the continuance of the present deplorable situation” confronting the college without making the strongest possible protest regarding API’s financial relationship with the state government. Furthermore, he complained of the “constant difficulty and unpleasantness” involved in dividing the state’s resources for higher education among competing institutions.

Farmers gather in front of Langdon Hall while attending Farmer's Week events in August 1929.

Farmers gather in front of Langdon Hall while attending Farmer's Week events in August 1929.  API alumni began voicing their dissatisfaction with Dowell’s administration when the 1924 football season ended with four wins, four losses, and one tie. On December 4, a group of Jefferson County alumni held a mass meeting in which they called for Dowell’s resignation. Although their reasons were vague, the situation quickly developed into a crisis. Trustee and Birmingham News publisher Victor Hansen charged that the group was motivated by an unsuccessful football season and that their complaint lacked substance. Associate counsel for the Jefferson County alumni group, Joel F. Webb, called for Dowell to be “tried before the board of trustees” and summoned all the faculty and students, except freshmen, to appear as witnesses against the president. On January 12, 1925, Governor Brandon called a special meeting of the board of trustees in his office. He read a letter from Victor Hansen, which called the governor’s attention to a newspaper statement by Attorney Webb, who questioned President Dowell’s ability to continue in office. Webb also challenged Hansen’s ability to judge the president because of a pro-Dowell editorial that had appeared in the Birmingham News. Hansen responded that it was the purpose of a newspaper to address such issues, and, moreover, as a member of the board of trustees, it was his duty to stay informed of issues relating to the college and to formulate opinions and policies. Hansen denied that this made him unfit to fairly judge President Dowell, but offered to submit the issue to the full board. The board affirmed its confidence in Hansen and called upon Webb to appear before them and specify his charges in writing.

API alumni began voicing their dissatisfaction with Dowell’s administration when the 1924 football season ended with four wins, four losses, and one tie. On December 4, a group of Jefferson County alumni held a mass meeting in which they called for Dowell’s resignation. Although their reasons were vague, the situation quickly developed into a crisis. Trustee and Birmingham News publisher Victor Hansen charged that the group was motivated by an unsuccessful football season and that their complaint lacked substance. Associate counsel for the Jefferson County alumni group, Joel F. Webb, called for Dowell to be “tried before the board of trustees” and summoned all the faculty and students, except freshmen, to appear as witnesses against the president. On January 12, 1925, Governor Brandon called a special meeting of the board of trustees in his office. He read a letter from Victor Hansen, which called the governor’s attention to a newspaper statement by Attorney Webb, who questioned President Dowell’s ability to continue in office. Webb also challenged Hansen’s ability to judge the president because of a pro-Dowell editorial that had appeared in the Birmingham News. Hansen responded that it was the purpose of a newspaper to address such issues, and, moreover, as a member of the board of trustees, it was his duty to stay informed of issues relating to the college and to formulate opinions and policies. Hansen denied that this made him unfit to fairly judge President Dowell, but offered to submit the issue to the full board. The board affirmed its confidence in Hansen and called upon Webb to appear before them and specify his charges in writing.

Dances at the Alumni Gym were popular events for Auburn students in the twenties.

Dances at the Alumni Gym were popular events for Auburn students in the twenties. In a series of events that were likened to a “Bolshevik Revolution,” the issue of Dowell’s removal as president of API resurfaced in the fall of 1927. A well-organized group of students began to discuss a course of action that would result in Dowell’s removal. On Sunday, October 2, following API’s loss to Clemson, “ten outstanding men on campus” met to discuss the situation. On Monday night, they called a meeting of twenty-four male students, “the Double Dozen,” who represented the junior and senior classes. The group agreed to dispatch representatives to interview alumni in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Columbus, Georgia. Trustee T.D. Samford suggested that the senior class select a representative to meet with the board’s executive committee, which he chaired. Samford and the senior class representative, L.S. Whitten, subsequently met with Governor Bibb Graves to discuss the matter. Meanwhile, a mass meeting of students called for Dowell’s removal. On October 14, Governor Graves convened a special meeting of the board of trustees where Whitten presented the students’ case before the governor, the board, and President Dowell. Whitten denied that football was “the cause of the unrest or disorder.” Under questioning from the board, he stated that Dowell probably was a good business manager, but neglected the human side of relations with students. He also spoke of an inability on the part of faculty to maintain classroom order. Finally, he mentioned the ill will created by “the Tuxworth affair,” a reference to the suspension of quarterback Frank E. Tuxworth for drinking. Student witnesses also mentioned a lack of cooperation among the president, faculty, and alumni. At least one board member suggested that certain alumni groups had instigated the student rebellion.

Dowell was convinced that athletics was the major factor behind criticism of his administration. He conceded to the board that he possibly should have spent “more time on the ball field, in the streets, or in social situations,” but argued that his primary energies had gone into resolving the school’s financial crisis. Three weeks later, on November 5, 1927, President Spright Dowell submitted his resignation.

The board selected Bradford Knapp, son of the distinguished agricultural reformer Seaman A. Knapp and president of Oklahoma A&M College, as Dowell’s successor. Victor Hansen, vice chair of the search committee, submitted Knapp’s name to the board, saying the committee had conducted a broad search and assumed that API needed a president who possessed a national reputation as an academic administrator. At the same meeting, T.D. Samford presented a resolution regarding the Alabama Teacher Training Equalization Fund, in which he complained that the state Board of Education had appropriated $20,000 from this source for API and $65,000 for the University of Alabama. He feared that, over the long run, this would give the University of Alabama a disproportionate influence over the state’s primary and secondary schools.

1929: Dedication of Alabama Extension Service office building,

Duncan Hall on API campus. L-R: Dr. F.W. Barnett, Dr. Bradford Knapp

(speaking),

Edward O'Neal, Mrs. W.F. Jefferson, Mrs. L.W. Spratling, Mrs.

L.N. Duncan.

State support and API’s ongoing rivalry with the University of Alabama occupied much of Knapp’s time during the first two years of his administration. Shortly after Knapp’s arrival in Auburn, T.D. Samford presented the report of a special board committee appointed to investigate the Teacher Training Equalization Fund. R.E. Tidwell, state superintendent of education, reasoned that if API continued with its plans for academic expansion, the net result would be the expensive duplication of programs throughout the state. Although Tidwell stressed cooperation and coordination, the tone of the Samford committee report was that this was a deliberate attempt to give the University of Alabama an unfair advantage in programs to train teachers in primary and secondary education. The committee also noted that this move coincided with a transitional period in API’s history, the implication being that Tidwell and his allies at the University of Alabama believed that API would be too weak to challenge the decision. Meanwhile, Governor Bibb Graves advised President Knapp that API was “qualified and fitted” to give teacher training in agriculture, but that the University of Alabama was “better fitted and qualified to do graduate teacher training work.”

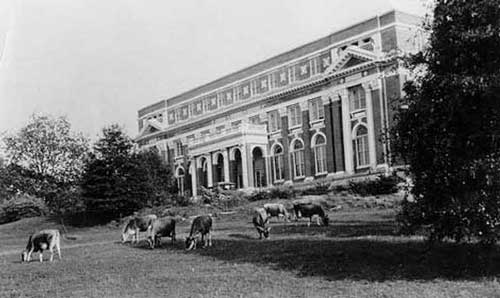

Cows graze in front of Comer Hall in the 1920's.

Cows graze in front of Comer Hall in the 1920's. The Great Depression worsened the financial crisis that President Knapp had faced when he took office. In 1930-31, the school’s enrollment reached an all-time high, which placed greater stress on an already aging physical plant and faculty workloads. From July, 1930, through February, 1931, API received no funds from the state, but Knapp praised the cooperation of the faculty and local business people during the emergency. He also complained to Governor Miller that the University of Alabama received a higher percentage of its quarterly appropriations than did API. By June, 1931, the college had applied for a $300,000 loan to offset the financial crisis created by the state’s inability to pay warrants from the building fund that had been approved four years earlier. In December, Trustee Samford informed Governor Miller that something should be done quickly to save API from “a disastrous experience.”

Early in 1931, while President Knapp and the board of trustees sought a solution to the school’s financial crisis, a new controversy began to emerge. For some time, Victor Hansen’s Birmingham News had published editorials attacking a cooperative grain purchasing agreement instituted by the Alabama Farm Bureau Federation and strongly supported by Luther N. Duncan and the Cooperative Extension Service. Hansen’s paper denounced Duncan as “a master of political trickery…probably without a peer, certainly without a superior, in Alabama.” In May, 1931, the Alabama Senate assembled for hearings on a bill that would have killed the Farm Bureau cooperative. Both the Extension Service and the Farm Bureau mustered such a turn out of support for the cooperative that the committee meeting was moved to Montgomery’s Crampton Bowl. Throughout the hearings, President Knapp consistently supported Duncan and the Extension Service, arguing that the proposed bill was not so much anti-extension as it was opposed to cooperation among farmers, who had a right to buy and sell cooperatively.

In February, 1932, Knapp issued a report to the board regarding the financial condition of the college. He argued that the financial crisis then besetting API began in the summer of 1931. It stemmed not from mismanagement, but rather from the state’s failure to disburse appropriations. He demonstrated that for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1931, API had received only one full quarterly appropriation. In essence, the school was operating on money borrowed from its employees, and Knapp urged the board to consider paying interest on back salaries. The alumni account was overdrawn by more than $18,000 and the athletic account was overdrawn by more than $81,000. Under these circumstances, he argued, financial planning was extremely difficult. Knapp augured that unless the school found another source of financial support, it might be forced to close for the 1932-33 academic year.

Unfortunately, Knapp faced another blow in the form of a 1932 Brookings Institute report on state and local government in Alabama. According to the report, API’s annual per-student expenditure was nearly twice that of the University of Alabama. The report speculated that either the University of Alabama was under-funded, or that API received too much state funding. In any event, the report recommended a unified administration for the state’s institutions of higher learning. Responding to the report, API officials contended that the University of Alabama’s significantly higher out-of-state enrollment distorted the report’s conclusions. Out-of-state enrollment factored into the equation, the University of Alabama spent 28.8 percent more than API per in-state student, which also meant that scarce Alabama tax dollars were being used to educate out-of-state students at the Tuscaloosa campus. Moreover, the University of Alabama had a higher percentage of students enrolled in relatively inexpensive liberal arts programs, whereas API had greater numbers enrolled in more expensive scientific programs.

On July 28, 1932, Knapp reported to the board that he had been operating under extreme stress and the board granted him a leave of absence for the month of August. They also offered to pay his salary during his absence, but Knapp refused to accept preferential treatment. Shortly thereafter, Knapp resigned as president of the Alabama Polytechnic Institute. From Montgomery, Governor B.M. Miller urged the board to appoint an administrative committee rather than an acting president and suggested that George Petrie, dean of the graduate school, Luther N. Duncan, director of the Extension Service, and J.J. Wilmore, dean of the Engineering School, serve as members.

Both Dowell and Knapp went on to successful academic careers after leaving API. Spright Dowell became president of Mercer University, where he remained in office for twenty-five years. Bradford Knapp became president of Texas Technological College, a position he held until death. Undoubtedly, both men faced only a slim chance for success at API. Dowell lacked a strong academic background and had not been an overwhelmingly popular choice to begin with. Moreover, Dowell was no match, politically, for the University of Alabama’s powerful supporters in Montgomery, and, rightly or not, he took the blame for API’s unsuccessful football season. Bradford Knapp had much stronger academic credentials, but he too lacked the political savvy necessary to press the school’s interests in the legislature. Additionally, what forward momentum Knapp brought to API was drastically undermined by the onset of the Great Depression. Knapp’s eventual successor brought a degree of political skill that drastically changed API’s fortunes.